Social Exchange Theory in Social Work: An Overview

Social work is, at its core, a profession built on the profound potential of human connection. Whether advocating for marginalized communities, counseling individuals in crisis, or mediating family conflicts, social workers harness the vitality of relationships to foster empowerment and equity. Consider this: a 2020 study by the National Association of Social Workers found that 70% of clients identified “trust in their social worker” as the most critical factor in achieving transformative outcomes. Trust, however, is not built in a vacuum—it emerges from meaningful exchanges where both parties perceive mutual value. This interplay of give-and-take lies at the heart of Social Exchange Theory (SET), a framework that brilliantly illuminates how individuals and groups navigate relationships through rational calculations of costs and benefits.

But why does this matter? In an era marked by systemic inequities—from racial disparities in healthcare to economic exploitation in underserved communities—understanding the “rules” governing human interactions becomes a powerful tool for justice. Social workers often rise to the challenge with questions like:

- How can a survivor of domestic violence reclaim agency after leaving an abusive partner?

- What inspires a community to mobilize for fair housing policies?

- How do clients discover renewed motivation to engage with support services after years of resistance?

SET provides an empowering lens to decode these dilemmas, offering actionable, hope-driven insights into the invisible economy of human behavior.

Defining Social Exchange Theory: Origins and Core Tenets

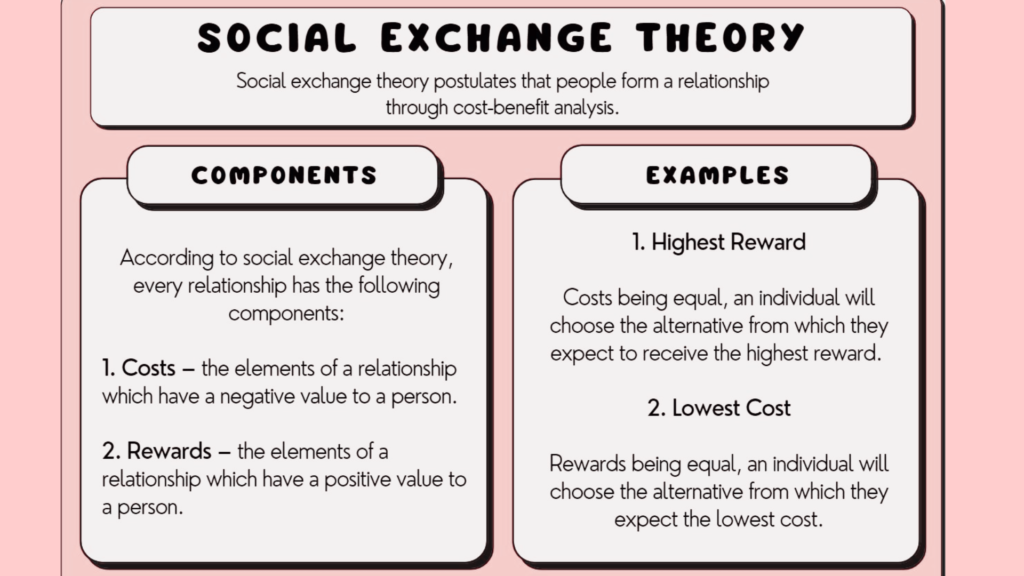

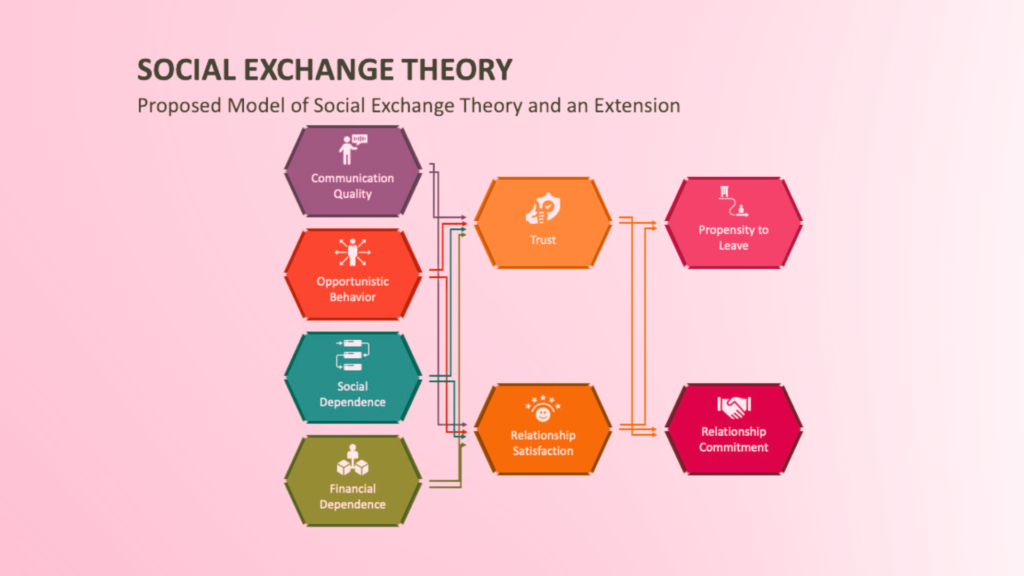

Social Exchange Theory (SET) posits that human relationships are shaped by subjective cost-benefit analyses. Rooted in pioneering work in behavioral psychology, economics, and sociology, SET emerged in the mid-20th century as scholars sought to explain social behavior through innovative rational choice paradigms.

Why SET Matters in Social Work

SET’s relevance to social work lies in its remarkable pragmatism. Unlike abstract theories, it offers a structured, empowering approach to:

- Decode Client Behavior with Compassion

- A teenager in foster care may reject stable placements due to perceived “costs” (loss of autonomy) outweighing “benefits” (safety), highlighting opportunities for trust-building.

- By building trust through culturally sensitive outreach, immigrant families can feel empowered to access public services, addressing concerns like safety while fostering inclusion and belonging.”

- Optimize Interventions with Precision

- A caseworker supporting a survivor of trafficking could use SET to strategically align tangible incentives (e.g., vocational training) with the client’s long-term empowerment.

- Champion Systemic Equity

- SET’s focus on power dynamics aligns seamlessly with social work’s mandate to challenge oppression. Advocating for policy changes to redistribute resources (e.g., healthcare, education) embodies SET’s vision of equitable exchanges.

Critically, SET honors the complexity of human agency—it acknowledges that “costs” and “benefits” are deeply subjective. A mother enduring domestic violence may wisely prioritize immediate safety (a perceived benefit) over the emotional cost of leaving, while a refugee might courageously weigh cultural alienation against the promise of asylum.

Social Exchange Theory in Psychology

In psychology, SET helps explain relationship dynamics, mental health challenges, and therapeutic outcomes. Therapists use its principles to decode behavior patterns and guide clients toward healthier interactions.

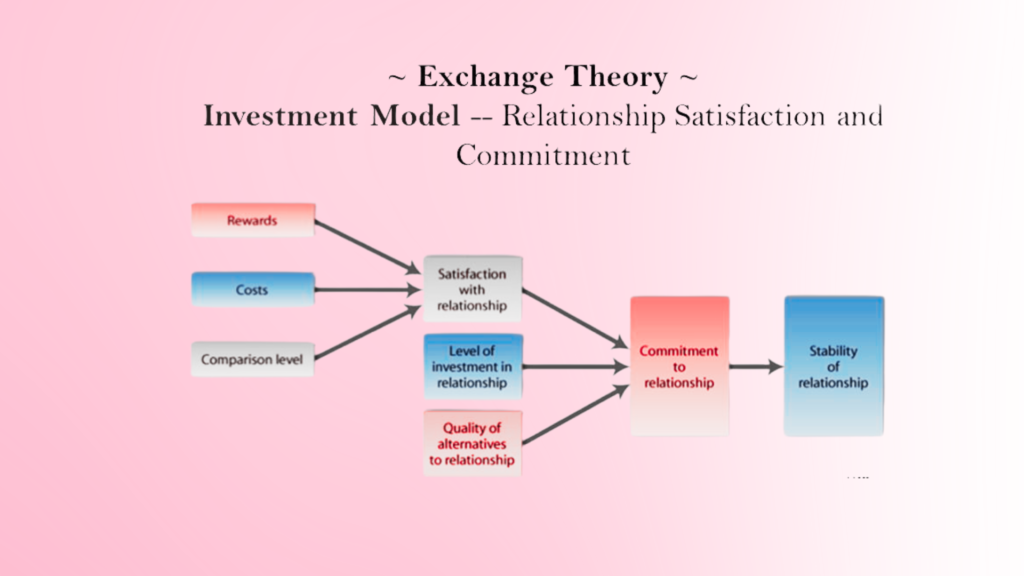

1. Understanding Romantic and Familial Relationships

Why do some relationships flourish while others crumble? SET argues that satisfaction depends on perceived equity. Partners who feel they’re contributing equally—whether through emotional support, chores, or finances—report higher relationship satisfaction. Conversely, imbalances invite renewal.

For example, a couple in therapy might realize one partner feels overburdened by household duties. The therapist could help them negotiate a fairer division of labor, restoring equilibrium.

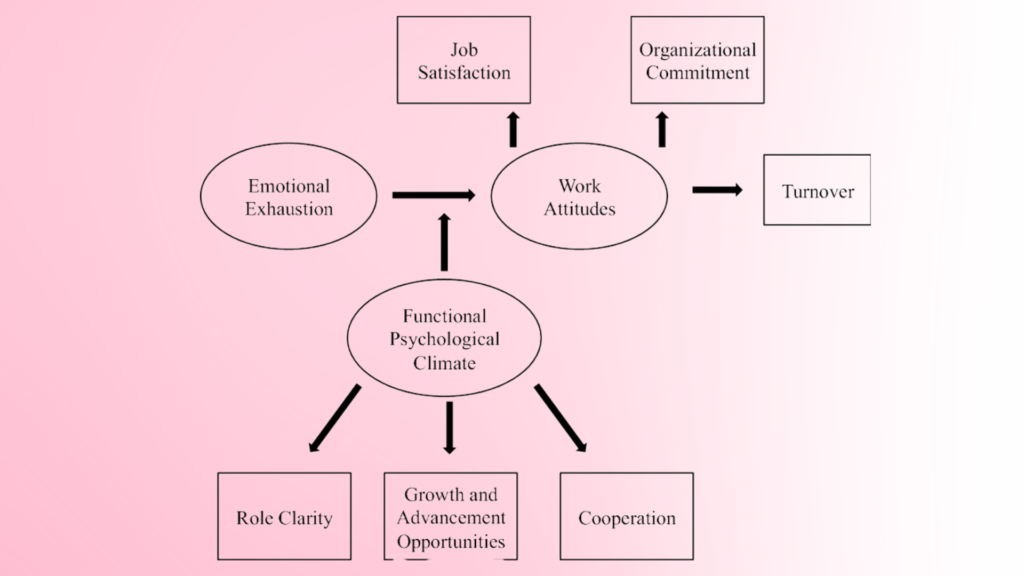

2. Workplace Dynamics and Employee Well-Being

SET also applies to professional settings. Employees evaluate their jobs based on exchanges like salary, recognition, and workload. Employers who prioritize fair compensation, growth opportunities, and work-life balance see higher retention and morale. Psychologists might use SET to address burnout by realigning workloads with rewards.

3. Therapeutic Interventions

Therapists incorporate SET to help clients:

- Set boundaries in toxic relationships (e.g., ending one-sided friendships).

- Shift toward balanced partnerships and mutual care

- Build networks that offer reciprocal emotional support.

A client recovering from codependency, for instance, might learn to prioritize relationships where their efforts are valued and reciprocated.

Theoretical Foundations of Social Exchange Theory

SET emerged as a groundbreaking bridge between disciplines, driven by scholars committed to decoding the rhythms of human interaction.

- George Homans (1958): Pioneered the link between behavior and reinforcement, illustrating how praise motivates a child’s compliance.

- Peter Blau (1964): Elevated SET by analyzing macro-level power structures, such as a social worker’s role in distributing housing vouchers.

- Thibaut & Kelley (1959): Introduced transformative concepts like the Comparison Level (CL), helping explain a survivor’s resilience in seeking shelter alternatives.

Core Principles of Social Exchange Theory

- Costs vs. Benefits: A refugee’s endurance of bureaucracy to secure asylum reflects profound hope in future stability.

- Reciprocity: Mutual respect between social workers and clients fuels lasting trust and collaboration.

- Power-Dependence Theory: Resource-sharing networks empower communities to break cycles of dependency.

Assumptions of SET

- Rationality as Empowerment: Clients’ choices, even in adversity , reveal agency and adaptive strength.

- Altruism’s Rewards: Acts of kindness, like a social worker’s advocacy, ripple into systemic change.

Application of Social Exchange Theory in Social Work

Understanding Client Relationships

- Building Trust Through Reciprocity: Collaborative goal-setting ignites client engagement, as seen when social workers share insights to deepen mutual respect.

- Case Management: Allocating housing slots based on urgency transforms lives by prioritizing dignity.

Group and Community Work

- Collective Action: Neighborhood coalitions lobbying for park renovations unite communities through shared vision.

Advocacy and Policy

- Medicaid expansion advocacy leverages SET’s principles to highlight societal gains from preventive care.

Challenges and Criticisms: Opportunities for Growth

- Cultural Adaptations: SET’s Western roots invite enriching dialogue with Indigenous gift economies, fostering communal well-being.

- Ethical Incentives: Thoughtful use of rewards, like meal vouchers in rehab programs, can uplift without compromising autonomy.

Social Exchange Theory Examples in Social Work

- Parent-Child Relationships: Parents invest time, resources, and care, expecting love, respect, or fulfillment in return.

- Customer Loyalty: Shoppers stay loyal to brands offering rewards (discounts, quality) that outweigh switching costs.

- Volunteer Work: Volunteers donate time/skills for intangible rewards (purpose, community connection).

- Online Dating: Users weigh effort (creating profiles, messaging) against potential rewards (companionship, romance).

- Teacher-Student Dynamics: Students engage in class for knowledge/grades; teachers invest effort for student success/professional satisfaction.

Each example reflects cost-benefit analysis and mutual exchange!

Important Theories and Practice Models Used in Social Work

- Psychodynamic Theory in Social Work

- Systems Theory in Social Work

- Social Learning Theory in Social Work

- Psychosocial Development Theory in Social Work

- Social Exchange Theory in Social Work

Future Directions: Innovation and Inclusion

- AI-Driven Tools: Predictive analytics promise to personalize interventions, identifying clients needing tailored support.

- Trauma-Informed Synergy: Blending SET with trauma care honors emotional complexity while fostering resilience.

Key Takeaways

- SET’s Brilliance: A pragmatic lens for understanding and uplifting human behavior.

- Ethical Synergy: Thrives when integrated with strengths-based, trauma-informed, and systems approaches.

- Future Promise: Continuous evolution ensures SET remains relevant across cultures and technologies.

Conclusion

SET’s strength lies in its adaptability and practicality, offering social workers a hopeful roadmap to decode behavior and design interventions. By pairing SET with cultural humility and systemic advocacy, practitioners can champion equity while honoring every client’s inherent worth.